The flow into private credit continues to be viewed by this writer as one of several factors helping explain the remarkable resilience of the US economic cycle despite 525bp of monetary tightening between March 2022 and July 2023.

On this point, there was an interesting article this quarter based on a recently published Moody’s report which has looked into how a growing number of companies financed by private credit are opting to increase their principal balance outstanding rather than paying cash to make interest payments, a practice otherwise known as “payments in kind” (PIK) (see Financial Times article: “Corporate debts mount as credit funds allow borrowers to defer payments”, 18 October 2024 and Moody’s report: “Business Development Companies – US: Q2 2024 Update: Asset quality erosion bites into net income”, 2 October 2024).

Moody’s estimates that 7.4% of the income reported by publicly traded private credit funds was in the form of PIK during 2Q24, the highest level since the rating agency began tracking the data in 2020.

The same article also notes that some private credit funds have seen 15% and 23% of their income earned in 2Q24 in the form of PIK.

While such PIK is counted as “income” each quarter, the article notes that the funds do not receive cash payments until the loan is refinanced or matures. This can create a potential liquidity crunch for private credit funds, which are reportedly required to pay out 90% of their income to investors even when they have not received hard cash on those loans.The potential positive aspect of PIK, however, is that it compounds at a higher rate than cash interest payments, assuming of course the loan is eventually paid back.

The resulting theoretical uptick in PIK income can make investment income in such private credit funds look more attractive to potential investors even if the rise in PIK income may well reflect growing financial stresses as a result of the increased cost of borrowing in recent years.

Still, the FT article also quotes lenders as saying that, if built into a loan at the start, PIK did not necessarily indicate stress.

This is because some credit funds offer PIK at the commencement of a loan to allow healthy businesses to direct their cashflow towards expansion plans.

All this is interesting since, as previously discussed here (see Breaking Down the Popularity and Risks of Private Debt, 18 June 2024), the flows into private credit have primarily gone into funding companies acquired by private equity where the debt has been put on the balance sheet of the acquired company, as is typical in the classic LBO model.

PE Owned Company Defaults on the Rise

On a related point, a recent Private Debt Investor article on another just published Moody’s report notes that the default rates of portfolio companies owned by the top 12 private equity funds tracked by Moody’s was 14.3% for the two years ending August compared with 7.1% for non-sponsored firms (see Private Debt Investor article: “Moody’s: Default rates for private equity-backed companies on the rise”, 14 October 2024).

The report also states that since the end of 2020 two thirds of corporate defaults have come from private equity-backed firms (see Moody’s report: “Private-equity backed companies face growing defaults, liquidity stress”, 10 October 2024).

The same article notes how Moody’s observes that private equity funds have borrowed against the funds’ combined assets to manage “diminishing” cash flow, a practice known as NAV loans, as well as tapping private credit and utilizing PIK techniques.

All this is testimony to the undoubtedly formidable financial engineering skills of those engaged in private equity; though, clearly, access to private credit flows has been a key support during the recent Fed tightening cycle.

That said, with an easing cycle now commenced there is clearly growing hopes for near-term relief.

A Recession Would Cause Big Problems for Private Debt and PE Funds

Meanwhile, the real risk facing both private credit and private equity is an economic downturn which leads to a marked decline in nominal GDP growth.

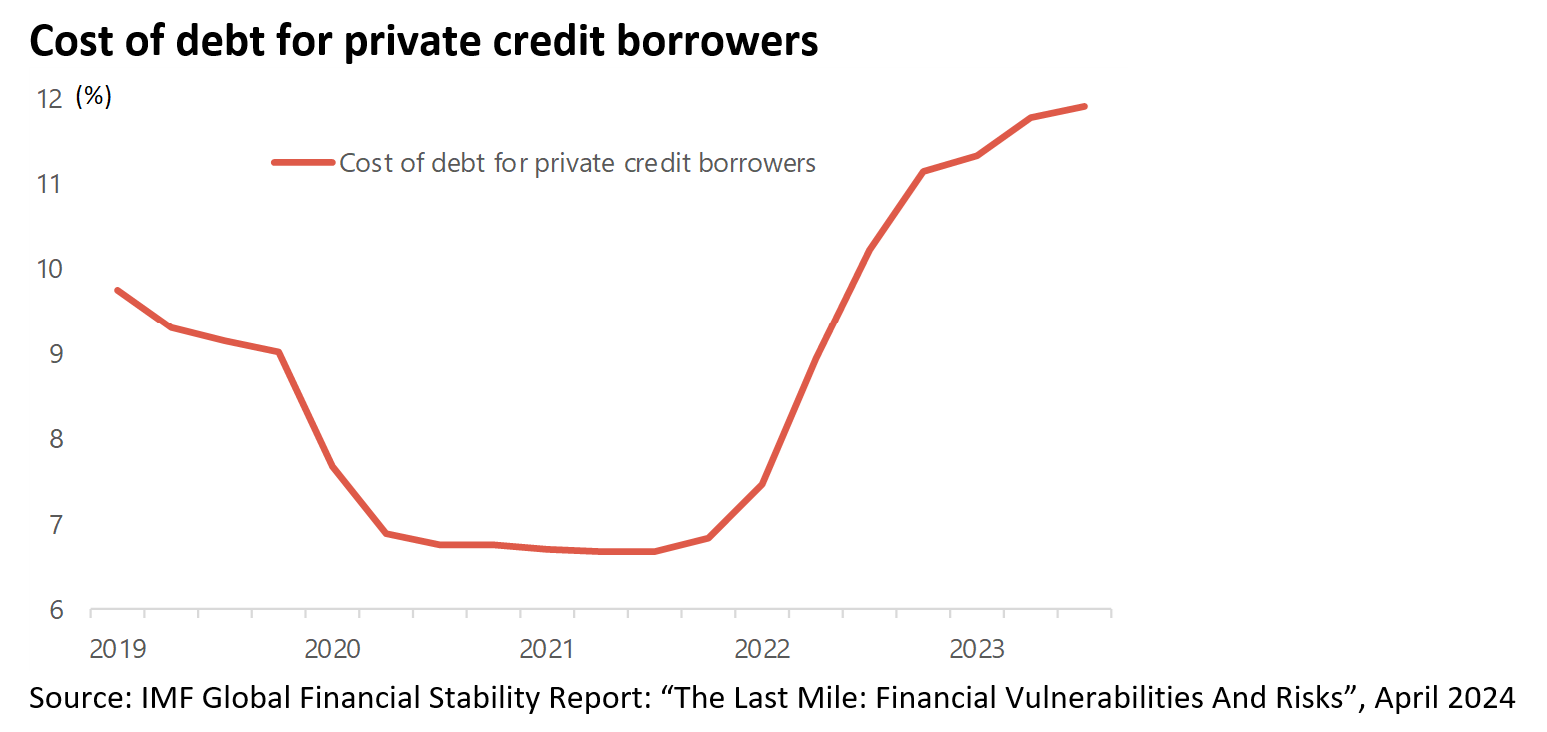

This would make the cost of borrowing of a private credit borrower, estimated at an average 11.9% in a previously referenced and highly recommended IMF report on private credit, very painful indeed (see Breaking Down the Popularity and Risks of Private Debt, 18 June 2024, and IMF Global Financial Stability Report: “The Last Mile: Financial Vulnerabilities And Risks”, Chapter 2: “The rise and risks of private credit”, April 2024).

In the absence of such a downturn, the base case has to be that the flows into private credit will continue.

Is the Lack of Regulation a Benefit or a Risk?

Meanwhile, the appeal of this asset class from the point of views of those managing private credit funds is that the assets are locked in while, unlike commercial banks, private credit fund managers are paid, so far as this writer understands it, on a percentage of assets under management and performance fees.

The above would seem to create an obvious incentive to engage in PIK, and indeed an incentive to “evergreen” loans in general.

This is the practice bank regulators are employed to watch out for.

But in the case of private credit there does not appear to be such a regulator.

Indeed the original argument for investing in private credit industry was the argument, and it was a very good one, that private credit was the market to enter given that the heavy regulation of the commercial banks in 2008 created a huge vacuum in the market for non-bank lenders to enter.

Meanwhile, amid the growing focus on private credit as its macro importance has grown, it is only fair to note that a SEC Commissioner defended the private credit market in a speech at a private credit event in October hosted by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) and law firm Mayer Brown (see SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce’s speech: “Temporarily Terrified by Thomas: Remarks on Private Credit before the SIFMA/Mayer Brown Private Credit Forum”, 15 October 2024).

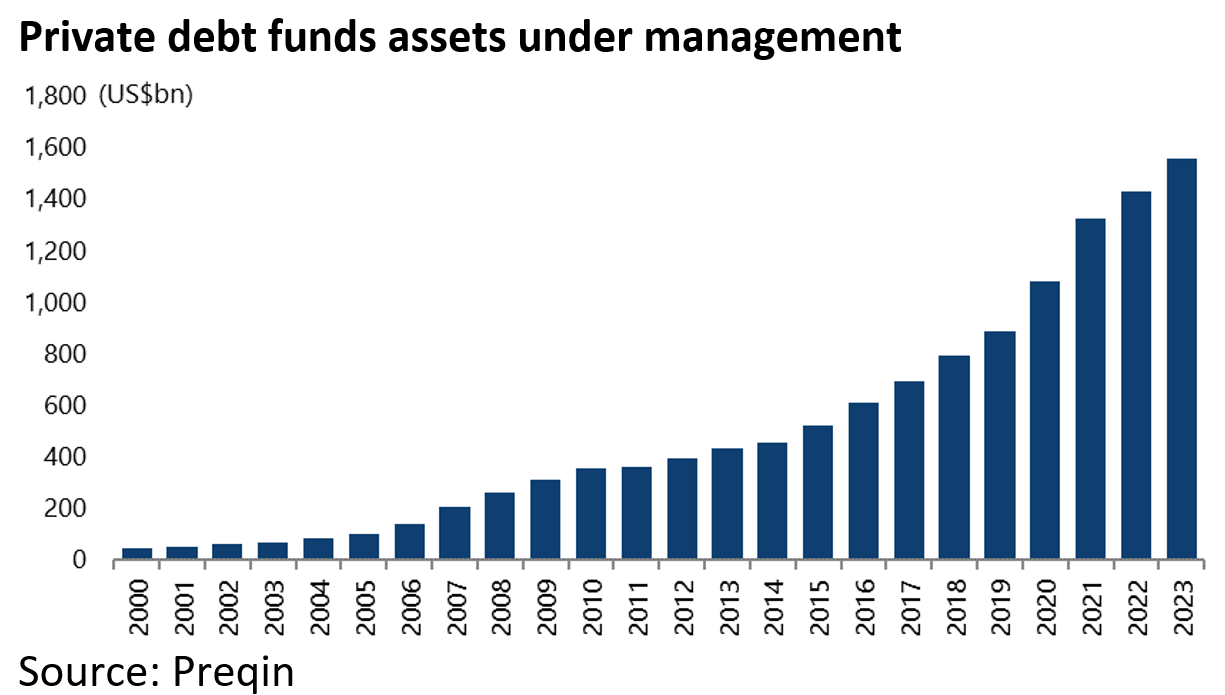

It should be noted that the estimated US$1.7tn private credit market has more than doubled in size since 2019.

Hester Peirce argued, according to an article in Pensions & Investments, that because private credit lenders typically hold loans until maturity, such lenders have an incentive “to conduct thorough due diligence, negotiate strong covenants and devise workable solutions if borrowers cannot pay”, as opposed to the slice and dice securitisation model which blew up in 2008 (see Pensions & Investments article: “SEC’s Peirce says private credit isn’t so scary”, 16 October 2024).

This is certainly an argument which has some merit though, as already noted, the ultimate stress test of this new asset class will only likely come in the context of a sustained economic downturn.

Meanwhile, what is crystal clear is that flows into private credit have played a significant role in alleviating cash flow stresses facing PE-owned companies during this recent Fed tightening cycle given that they borrowed using floating rate debt and were mostly unhedged as regards interest rate risk.

About Author

The views expressed in Chris Wood’s column on Grizzle reflect Chris Wood’s personal opinion only, and they have not been reviewed or endorsed by Jefferies. The information in the column has not been reviewed or verified by Jefferies. None of Jefferies, its affiliates or employees, directors or officers shall have any liability whatsoever in connection with the content published on this website.

The opinions provided in this article are those of the author and do not constitute investment advice. Readers should assume that the author and/or employees of Grizzle hold positions in the company or companies mentioned in the article. For more information, please see our Content Disclaimer.